Scent has become a marketing instrument. It programs our behaviour, shapes purchasing decisions, and even becomes part of a company’s—and our own home—identity. It has become a kind of noise, persistently affecting not only our senses but also our health.

This article is not opinion – it is analysis:

- What olfactory violence is, and how it affects our perception.

- Why smell reacts faster than consciousness – and why that matters.

- Why natural scents create ambience, while synthetic ones impose themselves.

- How the “noise” of scent feeds anxiety – even when we no longer notice it.

- And – how to create a home that doesn’t force us to defend against fragrance.

Scent – background music, not noise

Have you ever found yourself in a situation where smells felt invasive – crossing personal boundaries and flooding your sensory space – and your body didn’t respond with pleasure, but defence? Your head begins to pound, nausea creeps in, anxiety starts rising.

This isn’t the effect of traditionally unpleasant smells, like manure or decay. It’s the result of scents designed to please.

In my town, there are several shopping centres. They house attractive stores, but I’ve stopped visiting. As soon as I walk through the doors, I start to feel unwell and instinctively search for an exit. Business owners, believing in the power of fragrance, have created a scent “identity” for these places. The problem? It’s too strong. And it has a name – olfactory violence.

The word “olfactory” refers to anything related to the sense of smell. While you won’t find the term “olfactory violence” in official academic or legal documents, it’s gaining traction – because it accurately describes the sensory assault many of us experience: a kind of “perfume harassment.”

We now encounter olfactory violence not just in perfume boutiques, but in clothing shops, hotels, train stations, even children’s stores.

Scent noise is not just discomfort – it is chronic sensory overstimulation. It affects us like visual clutter or too much noise. At first, it irritates. Then it exhausts. Eventually, it overwhelms the senses, like pulling a heavy blanket over your head. The body protests. We just don’t always listen.

Smell reacts before thought

It was once believed that humans could identify around 10,000 distinct odours. But in 2014, researchers at Rockefeller University (USA) revealed that our capacity is far greater – we can distinguish over one trillion different smells.

The sense of smell is the only one that connects directly to the brain’s limbic system. When we smell something, the molecules bypass our conscious filtering systems and go straight to the areas responsible for emotion, memory, and instinct – such as the amygdala and hippocampus.

Scent signals reach the brain in less than 0.2 seconds – faster than sight or sound.

When we’re constantly exposed to the same smell (e.g. perfume or air fresheners), the brain’s receptors become desensitised – a process known as olfactory adaptation. Scientists explain that this suppresses conscious recognition, but not physiological impact. In other words, we might not notice a scent, but it continues to affect our nervous system. Over time, this can lead to fatigue and attention difficulties.

Chemical scents – neurotoxic

If you feel unwell in the presence of synthetic fragrances, you are not alone. A 2009 study showed that one in five people report negative reactions to public scents. Up to 34% experience symptoms from scented products – ranging from migraines to breathing issues. In Australia, the UK and Sweden, around 34–35% of adults reported experiencing migraines, asthma attacks or dizziness caused by fragrance exposure. Some (9%) were so severely affected, they lost jobs or had to avoid public places entirely.

A new medical category emerged: Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS), where individuals react to even tiny amounts of synthetic chemicals.

Why? Many synthetic scents contain volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which evaporate into the air and are inhaled. Some VOCs are already classified as neurotoxic or respiratory irritants. Others? They’re considered “safe” until proven harmful.

Why do we respond more negatively to synthetic than natural smells? The key lies in molecular diversity. Natural scents – like those from plants or beeswax – contain hundreds of complex compounds. They are dynamic. Synthetic scents are typically made from a small number of isolated or fabricated molecules. The result? Natural scents evolve and blend into the environment. Synthetic ones stand out – loud and static.

Another important distinction: natural scents dissipate quickly, reducing toxic load. Fragrances from wood or soil produce fewer and faster-evaporating VOCs than commercial air fresheners.

Not a myth – a fact

That synthetic fragrances can harm us is not a conspiracy theory – it’s proven. Here are just a few documented legal cases:

- In 1998, US teacher Judith Sanderson won a case to ban air fresheners in her school after proving they caused her migraines. She was legally recognised as a victim of “perfume harassment.”

- A police employee in Edmonds, Washington (USA) demonstrated in court that air fresheners triggered her migraines. Her employer had to limit their use in the office.

- The Marriott hotel chain faced a class action lawsuit in 2020. Guests claimed the hotel’s signature scent triggered health problems. The case remains unresolved.

- IFF (International Flavors & Fragrances) was fined $10,000 a day for emitting “offensive and contagious” odours from their Jacksonville, Florida, USA facility.

Why does olfactory violence exist?

Scent’s effect on the human body is scientifically established. But fragrance has become a tool of marketing. Brands discovered it builds emotional connections, drives purchases, and boosts recognition. This is called “sensory marketing.” Fragrance isn’t used to create ambience, but to control attention and behaviour.

The problem? These scents are almost always synthetic. They’re cheap, persistent, and aggressive. Designed to linger in the air, influence everyone, and cost very little.

We have laws regulating light, noise, even air quality. But fragrance is largely unregulated. The EU has acknowledged this gap. In 2021, a risk assessment recognised that “fragrant VOCs pose a danger to sensitive groups, though often treated as a cosmetic rather than health issue.”

Olfactory adaptation clouds judgement. People accustomed to perfumed environments “don’t notice the problem” – until they get sick. This creates a paradox: those who suffer are labelled “too sensitive”, while those who don’t notice assume all is well.

Does everything need to smell?

In modern culture, fragrance is equated with cleanliness, sophistication, even success. Fresh laundry, a new car, a scented candle – we’ve been taught that scent signals value.

Absence of fragrance? Often seen as a lack. Neutral smells = neglect.

Those who say “this smell makes me ill” are often told: “It’s just you,” “Everyone else loves it,” or “You’re too sensitive.” It’s taboo to question scent. People don’t want to seem weak or odd.

And few ever ask: What is this smell? What is it made of? What does it do?

Thus, we create a culture of silence.

Olfactory violence persists because our senses have become commercial targets, not trusted guides. Instead of creating safe and respectful spaces, fragrance is used to manipulate emotion and behaviour—without consent or escape. Until we reclaim conscious control over scent, it remains an invisible form of aggression.

FRAGRANCE INGREDIENTS ARE HIDDEN

Product labels usually say only “fragrance” or “parfum” – a legally permitted umbrella term that can mask hundreds of synthetic compounds.

! According to the European Commission, only 26 of over 3,000 fragrance chemicals must be disclosed on labels.

That means – WE DON’T KNOW WHAT WE’RE BREATHING.

How to restore your sense of smell – and your home

Most of the smells influencing us daily were not chosen by us. They’re marketing decisions we’ve absorbed without thinking. Think: detergent that “smells fresh for two weeks”, reed diffusers, “amber-wood candles” whose odour lingers even when extinguished.

What happens if we stop?

First step: Remove artificial fragrance temporarily

Try going a week without:

- fabric softener scent boosters,

- scented candles,

- diffusers and sprays.

In a few days, you might notice the return of subtle smells – beeswax, soap, fresh air, the scent of clean linen, a hint of dust, a trace of life.

How long does it take to regain your sense of smell?

Initial reset (48 hours) – Olfactory nerves begin recovering. Within a few days, many people report more vivid smells and tastes.

Medium-term recovery (2–8 weeks) – Studies suggest most people regain sensitivity within ~60 days.

Long-term restoration (6 months–15 years) – A study of 1,526 former smokers found that those who quit more than 15 years ago had smell function equal to non-smokers. Shorter-term quitters still had diminished capacity.

Why can recovery take so long?

Olfactory nerves may also be affected by: - poor circulation,

- chronic inflammation,

- genetic predisposition.

Second step: Replace scent with light

Scent is often used to set a mood. But light, materials and space do this too: - soft, natural lighting,

- warm materials like linen or wood,

- simplicity in decor.

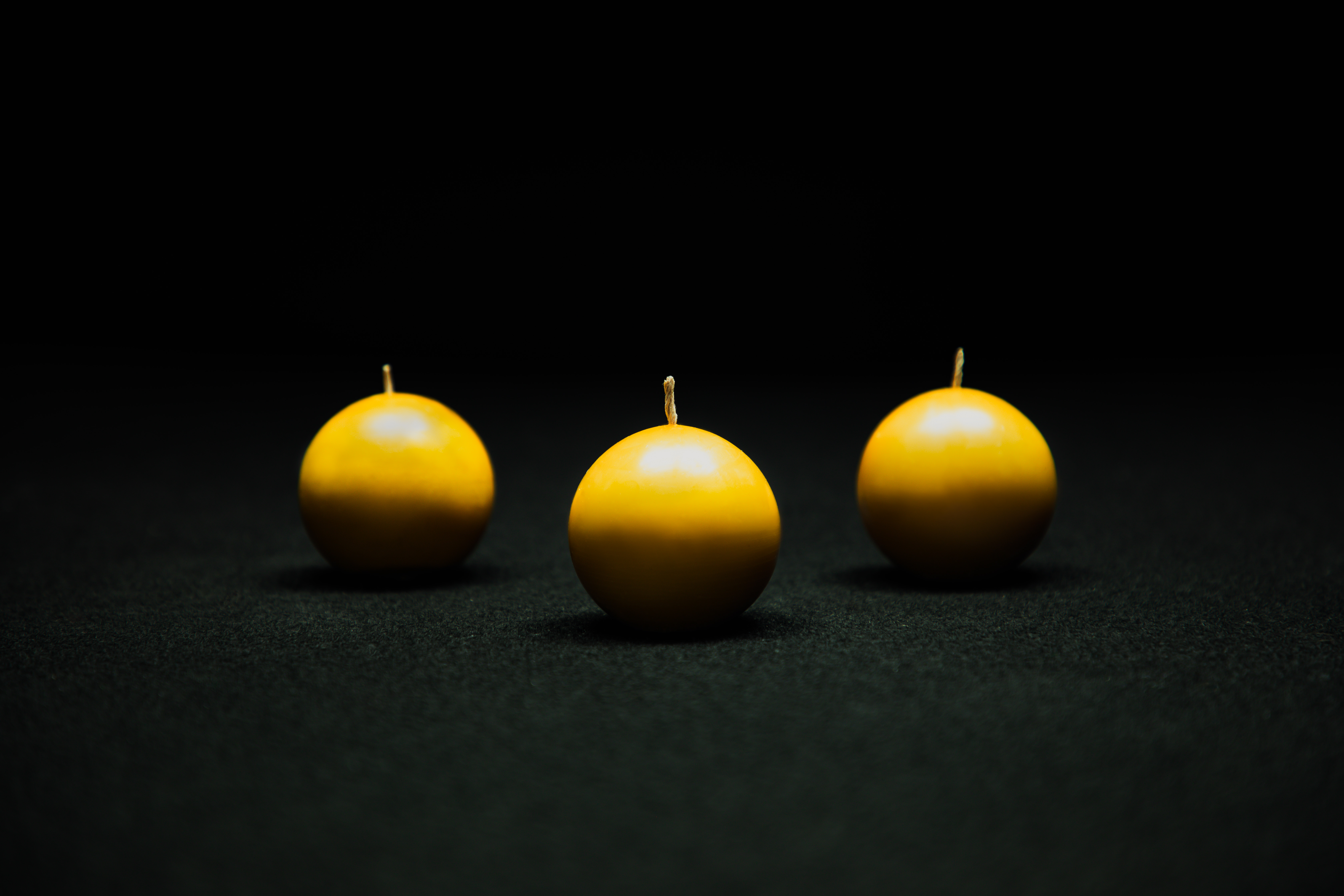

Beeswax candles help. Their soft amber glow creates calm. They emit almost no scent, and what they do release is mild, natural – not overpowering.

Third step: Choose scent that accompanies, not commands

Scent doesn’t need to disappear. But it should not dominate. Choose what is:

- natural (unrefined and unperfumed),

- subtle (not sprayed, but gently evaporating),

- ephemeral (not persistent or clashing with food, skin, or fabric).

Try: the soft scent of linen, raw beeswax, unscented soap, or a bit of untreated wood. Let smell be a background texture—not a headline.

Sources:

Bushdid, C., Magnasco, M. O., Vosshall, L. B., & Keller, A. (2014). Humans can discriminate more than 1 trillion olfactory stimuli. Science, 343(6177), 1370–1372.

Herz, R. S., & Engen, T. (1996). Odor memory: Review and analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3(3), 300–313.

Shepherd, G. M. (2004). The human sense of smell: Are we better than we think? PNAS, 101(8), 1602–1603.

Dalton, P., & Wysocki, C. J. (1996). The nature and duration of adaptation following long–term odor exposure. Perception & Psychophysics, 58(5), 781–792.

Caress, S. M., & Steinemann, A. C. (2009). Prevalence of fragrance sensitivity in the American population. Journal of Environmental Health, 71(7), 46–50.

Steinemann, A. (2016). Fragranced consumer products: exposures and effects from emissions. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 9(3), 861–866.

Sell, C. S. (2006). The Chemistry of Fragrances: From Perfumer to Consumer. Royal Society of Chemistry.

Perron, F., & Basset, J. (2015). Volatile Organic Compounds and Indoor Air Quality: A Review. Indoor and Built Environment, 24(5), 601–617.

https://www.classaction.org/news/marriott–hit–with–class–action–over–alleged–use–of–dangerous–fragrances–at–culver–city–courtyard–hotel?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://www.legalreader.com/lawsuit–wants–vile–odor–from–fragrance–factory–dealt–with/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Steinemann, A. (2017). Ten questions concerning fragrance–free policies and indoor environments. Building and Environment, 111, 251–257.

Singer, B. C., et al. (2006). Cleaning products and air fresheners: emissions and resulting concentrations of glycol ethers and terpenoids.

Skaarup, B., & Nielsen, G. D. (2002). Sensory irritation caused by exposure to common nonreactive VOCs in humans. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 75(7), 435–442.